Environmental monitoring and management is crucial for responsible airport operations. It allows the airport to understand its impact on the local environment and community and what can be done to manage and mitigate those potential impacts.

The system this airport uses is called ANOMS, which stands for Airport Noise and Operations Monitoring System which provides the Noise and Track Keeping (NTK) capability. It is a complex solution featuring both hardware in the form of remote sensors, radar data collectors as well as advanced analytical tools.

ANOMS uses a number of fixed or temporary noise monitors in the local area, these are generally located under or near flight paths. The monitors detect and send the noise levels every second 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to a central system.

A ‘noise event’ is created when the system detects noise exceeding the background or local noise level for an appreciable amount of time. This could be due to any number of factors, be it local birds, cars or an aircraft. By continuously monitoring the noise level and integrating data from Air Traffic Control (ATC) our systems can determine if the noise event was generated by an aircraft, or another source.

You can find out more by watching this video:

Data collection and noise event detection

The system combines data from remote noise monitors deployed in the local community and in proximity to runways and flight paths. These run 24 hours a day 7 days a week, continuously collecting and sending noise data through to ANOMS, creating ‘noise events’ when the noise level rises above the background noise level and meets pre-set thresholds.

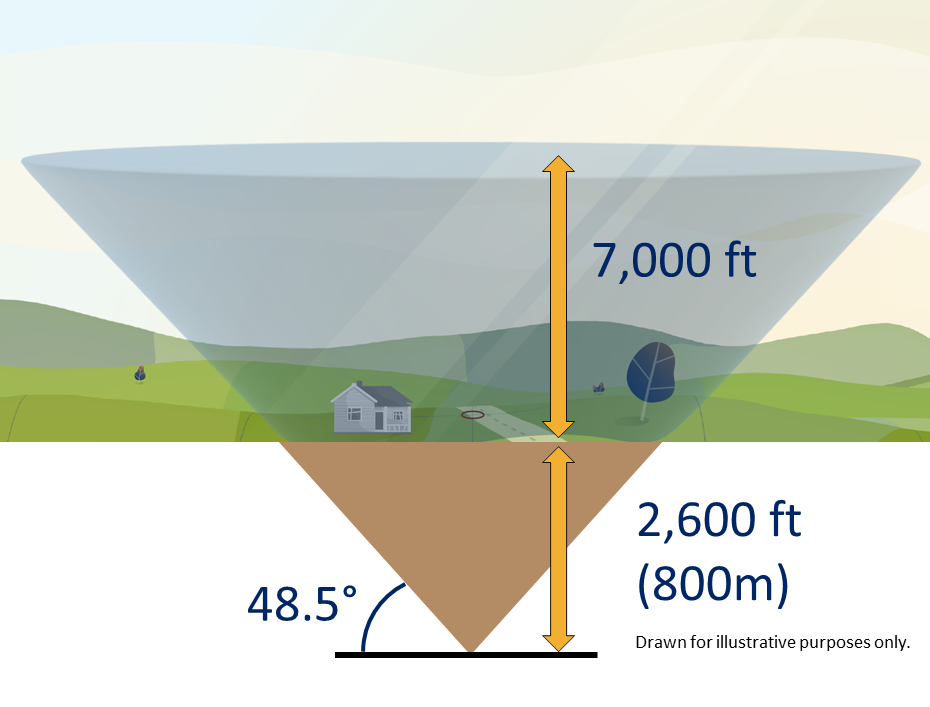

Flights are tracked using data direct from ATC radar systems, in effect it is the same data used by ATC to safely control aircraft in the sky. ANOMS uses this data to record the path flown by the aircraft and by identifying which noise monitors the aircraft flew close to and when. In simple terms, identify the noise events that were generated by that aircraft can be identified and linked.

The process is complex and, whilst it can identify noise events due to aircraft, it can also identify events that were not generated by aircraft. These are known as community events and could be generated by birds, wind, vehicles on a road or even emergency vehicle sirens. In effect, any noise that we could hear on a day-to-day basis that isn’t generated by an aircraft.

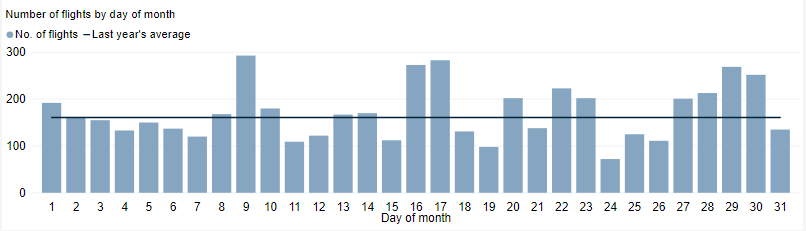

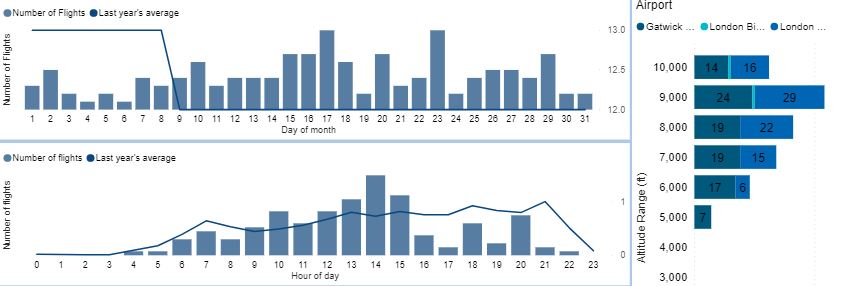

By considering the aircraft and community noise, a detailed picture of the local soundscape can be built, allowing the airport to understand the potential impact of operations in the local community.

Other data types are added to the system to gain a better insight into what happened and why. Weather data is another extremely useful feed – strong winds or thunderstorms may alter where aircraft fly, whilst clouds may reflect sound back towards the ground, changing how that noise is heard.

How the system is used

The ANOMS system is used by different stakeholders in the airport management structure:

- Community engagement teams can view enquiries, complaints and submissions from the local community, accessing the detailed data available within ANOMS to respond to the local community. This includes detailed weather and operational data to explore and analyse unusual operations.

- Operations teams can use the detailed reports to assess and continuously improve the airport.

- Management can assess trends, determine performance and provide direction.

In summary, the system can analyse a great deal, but two major items – quickly identify anything that was anomalous and discover why, and also monitor the day to day operations of the airport, presenting reports to management and the community. The historical data gained can then be used to plan for the future and improve operations.